I have had a little over a year to reflect on my journeys through southern Africa, and in that time I have continued to learn about and explore the concepts of race, privilege and oppression within the context of the development of art education, as well as in my own life, creative process, and teaching philosophies. Coming back from my adventures in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia, I felt better equipped to offer my future students a global art education, not just in representation of multicultural arts - but also in accuracy.

I was fortunate enough to have art class every year until I graduated high school, with trained teachers and wonderful facilities that provided materials - a privilege (or as I believe it should be: a right) that many American children are denied. However, within my own, very privileged, art education, I had little experience or exposure to art not made by dead white guys.

Now, those with whom I shared my elementary art classroom may be crying out, “But Trina! Do you not remember those African masks we made in 3rd grade?”

Why yes, I do remember. Mine is still sitting on a shelf somewhere in my parents’ home, collecting dust. It’s a monkey’s face made of embossed tinfoil, and its not too shabby, if I do say so myself. I also remember the Native American totem poles we made. And the Buddhist Mandalas.

But ask me what else I remember learning about these people, who created the art forms and techniques that many European artists appropriated from to get their fame and fortune (we all know the names Matisse and Picasso, right?). Go on, ask me. I don’t know squat. Even now, entering my fourth year of university classes, much of what I’ve learned about “third world” (and I use this term with quotations for good reason) art were from sources I had to seek out on my own, or literally travel across the globe to experience (another privilege I am very blessed to have).

So, for the vast majority of American students, even if they were lucky to have high levels of art education in their K-12 years, they move on to the real world with the interpretations of Non-Western art to be extremely limited to their indigenous roots and “primitive” (again, quotation marks are important here) qualities.

Our art education is what creates our visual culture. Your Disney animators and magazine photoshop-ers were all once wide-eyed third graders making African masks and totem poles in art class. So no wonder when it comes to our media’s representation of world cultures we fall miserably flat in demonstrating that like Americans, other citizens of the world are multidimensional, rich with subcultures and histories that are reflected in their contemporary art forms. Of course, there are whole other elements of capitalist propaganda that fuel these misrepresentations, but that’s an entirely different tangent for another time.

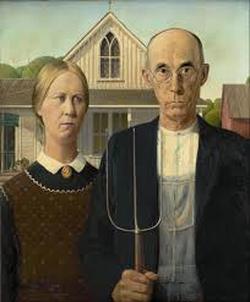

Wait, all Americans don't dress like this??

Wait, all Americans don't dress like this??

Imagine if you were from another country, and all you had ever learned about American art was stale portraiture. That’s it. You think - “American art” and immediately your mind jumps to “American Gothic” - a boring ass white couple in front of their farmhouse. No offense to Grant Wood, but YAWN. Now imagine that American media didn’t hold such a global influence, and your weak art education was pretty much your only exposure to American visual culture. You would begin to associate all Americans with this stale image of an older couple, glaring menacingly at the painter with pitchfork in hand. Maybe one day you would meet an American, and your first question for them would be about their farm, and they would be quite confused, because in reality this is a very narrow image of American culture, and probably doesn’t apply to them.

It may sound ridiculous, but this is how global art is being represented in our classrooms and media, and it is especially true for cultures of color. This affects almost every aspect of our lives - from how we treat others to how we see ourselves. And because of the American media’s powerful influence on the world, it even influences the discourse of the global art itself, forcing many to exploit their own cultures for economic gain in a tourist driven arts market, and furthering the cycle of global misrepresentation.

A group selfie on the first day of class!

A group selfie on the first day of class!

This June, I was given another incredible opportunity to go abroad and focus precisely on the issues that piqued my interests while in Africa. This time, I was heading out with a group of fellow art teachers to explore the history and influence of Jamaican arts and culture at the Edna Manley College of Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, and its relationship to the development of art education practices within the Caribbean.

I found again that the one-dimensionality of what we think of as “Jamaican art”, or even “Jamaican culture” in general, was hardly a reflection of reality. Among the souvenirs my friends expected to receive among my return home were beach-y seashell bracelets, hand woven Rastafarian hats and, of course, weed-related paraphernalia. These items were indeed plentiful - in the souvenir marts and gift shops of all the popular tourist attractions. The actual art - what we saw in the galleries, exhibitions at the arts colleges, performances in arts incubators, even what was being taught in the high schools - was far different from the craft culture we have come to expect from island nations.

Now, before I continue, I want to clarify one thing. I am by no means denying the existence or importance of these art forms. They have very real roots in the history of Jamaica, the construction of their artistic culture, and the creation of a national identity post-colonization. I am not critiquing the craft arts of street markets geared toward tourists as “lesser” than that of the works in The National Gallery or at the Edna Manley College. I am simply saying that there is a whole other dimension to the contemporary art world of the Caribbean besides sun, sand and sea that we aren’t seeing portrayed in mainstream media or taught in our “globally inclusive” art classrooms.

I found again that the one-dimensionality of what we think of as “Jamaican art”, or even “Jamaican culture” in general, was hardly a reflection of reality. Among the souvenirs my friends expected to receive among my return home were beach-y seashell bracelets, hand woven Rastafarian hats and, of course, weed-related paraphernalia. These items were indeed plentiful - in the souvenir marts and gift shops of all the popular tourist attractions. The actual art - what we saw in the galleries, exhibitions at the arts colleges, performances in arts incubators, even what was being taught in the high schools - was far different from the craft culture we have come to expect from island nations.

Now, before I continue, I want to clarify one thing. I am by no means denying the existence or importance of these art forms. They have very real roots in the history of Jamaica, the construction of their artistic culture, and the creation of a national identity post-colonization. I am not critiquing the craft arts of street markets geared toward tourists as “lesser” than that of the works in The National Gallery or at the Edna Manley College. I am simply saying that there is a whole other dimension to the contemporary art world of the Caribbean besides sun, sand and sea that we aren’t seeing portrayed in mainstream media or taught in our “globally inclusive” art classrooms.

Detail of an installation by Nadine Hall, Fibre artist

Detail of an installation by Nadine Hall, Fibre artist

Instead of seashell necklaces and hand-carved elephant sculptures, our first day on campus we were greeted with amazing installations in jewelry, paintings, wire/metal work, fiber arts, graphic design, architecture and more, all as a part of the visual arts students’ senior exhibitions. We spent some afternoons wandering these exhibits, getting lost in the many ideas, the beautiful artworks and intricate installations that captivated us. The artists were often present, eager to talk with us and share their work as well as their processes and journeys in creation.

In the first two days of class, we learned the history of the region, along with its arts and musical accomplishments through lectures from Petrona Morrsion and Ibo Cooper, both talented artists and speakers in their own rights. The pre-trip readings we completed prior to our departure also went in to great depths about the history of Jamaica and other areas of the Caribbean, particularly diving in to the affects of this trajectory on the development of artistic and musical movements within the island areas. This crash course in Caribbean history was all new territory for me, but because of my exposure from mainstream media, I was somewhat familiar with the more famous Jamaican creative byproducts such as Reggae and Ska. What I didn’t know was all that those art forms stood to represent in terms of the context of political and social oppression its creators were facing at the time, and just how deep, complex and intertwined each movement truly was.

We were able to see this history, and its present affects on Jamaican society, through the contemporary art and art classrooms we experienced on the remainder of the trip. Even among the diversity in mediums, techniques and conceptual elements, I soon discovered that there was an underlying theme within the student work, as well as in the rest of the contemporary art we saw while on the island, addressing the big idea of identity, specifically as it applies to Jamaica on a national level. This theme was the central focus of the many readings by Rex Nettleford, a Jamaican dancer, writer and sociologist who worked extensively with analyzing the cultural construction of Jamaica’s image post colonization, especially in conjunction with the Rastafarian movement.

In the first two days of class, we learned the history of the region, along with its arts and musical accomplishments through lectures from Petrona Morrsion and Ibo Cooper, both talented artists and speakers in their own rights. The pre-trip readings we completed prior to our departure also went in to great depths about the history of Jamaica and other areas of the Caribbean, particularly diving in to the affects of this trajectory on the development of artistic and musical movements within the island areas. This crash course in Caribbean history was all new territory for me, but because of my exposure from mainstream media, I was somewhat familiar with the more famous Jamaican creative byproducts such as Reggae and Ska. What I didn’t know was all that those art forms stood to represent in terms of the context of political and social oppression its creators were facing at the time, and just how deep, complex and intertwined each movement truly was.

We were able to see this history, and its present affects on Jamaican society, through the contemporary art and art classrooms we experienced on the remainder of the trip. Even among the diversity in mediums, techniques and conceptual elements, I soon discovered that there was an underlying theme within the student work, as well as in the rest of the contemporary art we saw while on the island, addressing the big idea of identity, specifically as it applies to Jamaica on a national level. This theme was the central focus of the many readings by Rex Nettleford, a Jamaican dancer, writer and sociologist who worked extensively with analyzing the cultural construction of Jamaica’s image post colonization, especially in conjunction with the Rastafarian movement.

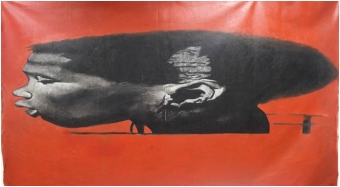

A painting by Twaunii Sinclair featured in the exhibition

A painting by Twaunii Sinclair featured in the exhibition

One student artist in particular addressed similar concerns in his senior installation that Nettleford raised during the 70’s to 90’s. Twaunii Sinclair’s large scale paintings featured the stretched and distorted faces of black men held captive by an antiquated torture device around the neck. He talked about how their identities as Jamaicans, and specifically as black men, have been shaped and distorted by the influences of oppression, even centuries after emancipation and years after independence. He also spoke that although they be brutal and unpleasant, it is these distortions and struggles that must be accepted as part of the complex creation of themselves.

So much of the creative development within Jamaica has come from the desire to free oneself from the past. The Rastafarian movement as a whole cried for a return to Africa (in both literal and metaphorical terms) and aimed for a separation from the wider society that claimed Jamaica was a nation made of many, instead declaring it a black country, built by slaves and influenced by the carried cultures of their African roots.

Nettleford discusses how the exchange (and force) of cultural engagement have shaped racial and national identities within the Caribbean. He examines the Rastafari movement, as well as the views of the European Jamaicans who believe that their lives and influences from the “primitive black” citizens are distinct and separate, operating as a one way cultural exchange. The denial of their Creolization allows for the ongoing construction of an “us-vs-them” dichotomy and a continual imbalance in social, political and economic power among races.

So much of the creative development within Jamaica has come from the desire to free oneself from the past. The Rastafarian movement as a whole cried for a return to Africa (in both literal and metaphorical terms) and aimed for a separation from the wider society that claimed Jamaica was a nation made of many, instead declaring it a black country, built by slaves and influenced by the carried cultures of their African roots.

Nettleford discusses how the exchange (and force) of cultural engagement have shaped racial and national identities within the Caribbean. He examines the Rastafari movement, as well as the views of the European Jamaicans who believe that their lives and influences from the “primitive black” citizens are distinct and separate, operating as a one way cultural exchange. The denial of their Creolization allows for the ongoing construction of an “us-vs-them” dichotomy and a continual imbalance in social, political and economic power among races.

A classroom at Titchfield High, Port Antonio

A classroom at Titchfield High, Port Antonio

In the same ways that Nettleford argued that Creolization in the arts has become a complex blending of cultures to a point of difficult distinction, lecturer and artist Petrona Morrison asserted that Jamaican art is not always easy to identify because of its complexity of being rooted in such a rich historical context. We saw this reflected in the work featured in the National Gallery that ranged from historic to contemporary. The artistic struggle to visually represent an authentic Jamaican identity increases, but also becomes richer, as there is a greater acceptance and understanding of the many cultural influences in the Caribbean.

Having spent much time discussing the struggles in trying to shape an authentic Caribbean identity within arts and culture, we began dissecting the role education, and art education in particular, can play in the creation of a Jamaican national image. Now having a background in the history of colonial oppression and influence in Jamaica, we were able to listen to those who grew up on the island and understand their experiences within their own art education and how the field developed over time. One art teacher, Michael Layne, born and raised in Port Antonio, told stories of how much of his own education was rooted in English standards, from content to structure to assessment to art instruction. These anecdotes go hand in hand with the assertions of Nettleford who argues that media, education and cultural forces should all come from within the island in order to avoid a social and economic dependence on other nations, as well as to help build an authentic cultural position.

Having spent much time discussing the struggles in trying to shape an authentic Caribbean identity within arts and culture, we began dissecting the role education, and art education in particular, can play in the creation of a Jamaican national image. Now having a background in the history of colonial oppression and influence in Jamaica, we were able to listen to those who grew up on the island and understand their experiences within their own art education and how the field developed over time. One art teacher, Michael Layne, born and raised in Port Antonio, told stories of how much of his own education was rooted in English standards, from content to structure to assessment to art instruction. These anecdotes go hand in hand with the assertions of Nettleford who argues that media, education and cultural forces should all come from within the island in order to avoid a social and economic dependence on other nations, as well as to help build an authentic cultural position.

Students at work in Excelsior High School

Students at work in Excelsior High School

Michael Layne discussed his role in developing art education as a step away from European control and influence by integrating local values, teachers and artists not only to instruct students but also to change the way that art education was approached. When we went to visit the schools, we can see some of these changes in action. Looking through examples of student work at Excelsior high school, our first stop, I was pleased to find that within the student journals (a graduation requirement for arts students) there was a higher emphasis on writing and research that involved local and contemporary artists over the classics and European masters.

However, it was also still obvious that similar educational policies affect Jamaica as they do in the U.S.

After this first visit, a peer brought up a point that I initially had not considered. She too was glad about the local curriculum, but pointed out that although there was more flexibility in relevance to the content – the guidelines, standards, assessments and system of art education as a whole was largely still operating in a European structure. Much like the politics and practices that Nettleford discussed, it was simply a process of the black man taking a seat in a white office and calling it authentic Caribbean empowerment, when in reality, it denies the Jamaican people the ability to design and implement their own policies and infrastructures that would better suite their needs as an independent nation of self-governed people. There was still a heavy emphasis on formalist principles in art such as traditional and realistic rendering, “correct” composition, and technical skill - despite the conceptual and modern prowess we observed at the collegiate level. The art education of Jamaica was catching up to the modern art movements of Jamaica, but it still had a ways to go. This is perhaps where I found the most similarities to U.S. art education - because of this forced and foreign structure there becomes a larger burden of needing to standardize the education process.

Additionally, a higher emphasis on math and science careers, value placed on “training rather than education” (another common theme throughout Nettleford’s work) and lack of funding for both arts and education programming are detrimental to the development of a uniquely Jamaican education system, therefor causing more issues for the formation of an authentic artistic and cultural identity.

The underfunding and underrepresentation of arts in our schools is a global crisis, but I fear it holds a larger detriment to the nations that very identity stems from its cultural roots in the arts. From hidden slave pottery to reggae music, the people of Jamaica have relied on the arts as an outlet for freedom in times where it seemed they had none. If art education becomes less accessible and more mandated to those who need it most, how can Jamaica, or any other country for that matter, build its own society on its own terms and create an authentic identity within a world where it is already widely appropriated and debated on an international level?

However, it was also still obvious that similar educational policies affect Jamaica as they do in the U.S.

After this first visit, a peer brought up a point that I initially had not considered. She too was glad about the local curriculum, but pointed out that although there was more flexibility in relevance to the content – the guidelines, standards, assessments and system of art education as a whole was largely still operating in a European structure. Much like the politics and practices that Nettleford discussed, it was simply a process of the black man taking a seat in a white office and calling it authentic Caribbean empowerment, when in reality, it denies the Jamaican people the ability to design and implement their own policies and infrastructures that would better suite their needs as an independent nation of self-governed people. There was still a heavy emphasis on formalist principles in art such as traditional and realistic rendering, “correct” composition, and technical skill - despite the conceptual and modern prowess we observed at the collegiate level. The art education of Jamaica was catching up to the modern art movements of Jamaica, but it still had a ways to go. This is perhaps where I found the most similarities to U.S. art education - because of this forced and foreign structure there becomes a larger burden of needing to standardize the education process.

Additionally, a higher emphasis on math and science careers, value placed on “training rather than education” (another common theme throughout Nettleford’s work) and lack of funding for both arts and education programming are detrimental to the development of a uniquely Jamaican education system, therefor causing more issues for the formation of an authentic artistic and cultural identity.

The underfunding and underrepresentation of arts in our schools is a global crisis, but I fear it holds a larger detriment to the nations that very identity stems from its cultural roots in the arts. From hidden slave pottery to reggae music, the people of Jamaica have relied on the arts as an outlet for freedom in times where it seemed they had none. If art education becomes less accessible and more mandated to those who need it most, how can Jamaica, or any other country for that matter, build its own society on its own terms and create an authentic identity within a world where it is already widely appropriated and debated on an international level?

A photo from Dunn's River Falls

A photo from Dunn's River Falls

This appropriation of traditional art forms was undeniable once we were off of the campus that actively embraced movements in contemporary arts. It was no secret that we were foreigners everywhere we went, and on an island where much of the economic prowess comes from catering to tourists, we were very valued customers. Like any good sales workers, many were very good at marketing their products in telling us what they thought we would want to hear. Gift shops and market sheds set up on the side of the mountain roads promised the most authentic Jamaican crafts and jewelry - most of which were identical to the items I bought in Southern Africa - “traditional” carvings and “tribal” bracelets. On our way to Dunn’s River Falls (a popular park and tourist area), we stopped by the side of the road to explore a small strip of tiny stands catering to visitors like us. Like the curio marts in southern Africa, as soon as we stepped off of our bus we were identified, greeted and escorted in to the tiny sheds, some held up by sticks and covered in tarps. As they tried selling their products, there is a noticeable difference in the way they talk compared to how the locals we were working with on campus. They were not just selling us crafts - they were selling us their culture, in a way that us as Americans would have expected from a Jamaican art experience.

A man who had offered me a pair of free beaded earrings (compliments to my brightly colored hair which garners me attention abroad and at home) gave me a choice of colors. “Would you like ones with Jamaica colors?” He dangled black, yellow and green (the colors of the Jamaican flag) beads from his right hand. “Or, would you like ones with Bob Marley colors?” From his left he held out red, yellow and green beaded jewelry.

Had this been our first day on the island, I may not have batted an eye, but we had already begun dissecting the art and culture of the Caribbean enough for me to understand that he had simplified the choices in to phrases marketed at his foreign audience.

In the museums and lectures we had on the Rastafarian movement and even in the lessons on Bob Marley himself, never were these colors referred to as “Bob Marley colors”. Because they aren’t Bob Marley’s colors - they belong to the Rastafari movement, symbolizing a return to Africa with the use of the colors from the Ethiopian flag. But Bob Marley is perhaps the most famous Rastafari, and his music and global presence is some of the only exposure to the movement that many visitors to Jamaica have ever had.

I wondered how many people that man had sold earrings to in the past. At some point, he decided that the product was best marketed as “Bob Marley colors”. I also wondered how many people had gleefully bought the jewelry, toting it back to their home country and sharing with their friends and family how they were given very authentic Bob-Marley-colored jewelry made in a Traditional Jamaican Hut by Local Native Artist Man ©.

A friend of mine recently wrote this brief essay on some of the effects tourism can have, including this cultural misrepresentation and “staged authenticity”. His questioning of the economic benefits of tourism coincide with my own questions surrounding the cultural exchange benefits - by trying to bring back “authentic” images of other nations in to our art rooms, can we be doing more harm than good? How can we teach our students about the roots of tradition and craft within global art without contributing to the many stereotypes and misconceptions being thrown at them by media images? I want to be able to bring art from around the world to my students, but as a privileged white woman, I have to be careful about how I am representing these other cultures.

Two weeks in Jamaica was certainly not enough time to even begin to find answers to all of my questions, and if anything the experience made me more curious as to how I can improve myself as an American art educator. But sometimes the best learning experiences leave you with more questions than answers.

A man who had offered me a pair of free beaded earrings (compliments to my brightly colored hair which garners me attention abroad and at home) gave me a choice of colors. “Would you like ones with Jamaica colors?” He dangled black, yellow and green (the colors of the Jamaican flag) beads from his right hand. “Or, would you like ones with Bob Marley colors?” From his left he held out red, yellow and green beaded jewelry.

Had this been our first day on the island, I may not have batted an eye, but we had already begun dissecting the art and culture of the Caribbean enough for me to understand that he had simplified the choices in to phrases marketed at his foreign audience.

In the museums and lectures we had on the Rastafarian movement and even in the lessons on Bob Marley himself, never were these colors referred to as “Bob Marley colors”. Because they aren’t Bob Marley’s colors - they belong to the Rastafari movement, symbolizing a return to Africa with the use of the colors from the Ethiopian flag. But Bob Marley is perhaps the most famous Rastafari, and his music and global presence is some of the only exposure to the movement that many visitors to Jamaica have ever had.

I wondered how many people that man had sold earrings to in the past. At some point, he decided that the product was best marketed as “Bob Marley colors”. I also wondered how many people had gleefully bought the jewelry, toting it back to their home country and sharing with their friends and family how they were given very authentic Bob-Marley-colored jewelry made in a Traditional Jamaican Hut by Local Native Artist Man ©.

A friend of mine recently wrote this brief essay on some of the effects tourism can have, including this cultural misrepresentation and “staged authenticity”. His questioning of the economic benefits of tourism coincide with my own questions surrounding the cultural exchange benefits - by trying to bring back “authentic” images of other nations in to our art rooms, can we be doing more harm than good? How can we teach our students about the roots of tradition and craft within global art without contributing to the many stereotypes and misconceptions being thrown at them by media images? I want to be able to bring art from around the world to my students, but as a privileged white woman, I have to be careful about how I am representing these other cultures.

Two weeks in Jamaica was certainly not enough time to even begin to find answers to all of my questions, and if anything the experience made me more curious as to how I can improve myself as an American art educator. But sometimes the best learning experiences leave you with more questions than answers.

Though small and hard to come by, there are many steps being made in the right direction for a healthier marriage between tourism and art. One place we visited in Kingston, Nanook, is aiming to do just that by providing a small arts space by day and a social spot by night, allowing artists to have a space to both create and share their work.

Listening to founder Joan Webley share her story and the process it took to develop the community and arts incubator she has been fostering since 2008 was incredible and inspiring. Her ups and downs in creating and operating Nanook illustrated some of the many hardships Jamaican cultural and creative organizations face in trying to engage and generate an authentic community without a stage for tourist attraction. She shared that a lot of her struggle has come in finding a balance between the authenticity of the arts and local community while still making the space accessible to tourists, so that she could bring them a more accurate image of Jamaican arts and culture.

The night that we visited Nanook was a special occasion for the space, a fundraiser and kick off of their United Purpose (UP) Tour, "a curated display of Jamaica's unique and creative cultural arts industries. It is a traveling caravan of eleven artists, all of whom are exceptional in their own fields, venturing into Europe to bring a complete Jamaican experience to the open markets."

Listening to founder Joan Webley share her story and the process it took to develop the community and arts incubator she has been fostering since 2008 was incredible and inspiring. Her ups and downs in creating and operating Nanook illustrated some of the many hardships Jamaican cultural and creative organizations face in trying to engage and generate an authentic community without a stage for tourist attraction. She shared that a lot of her struggle has come in finding a balance between the authenticity of the arts and local community while still making the space accessible to tourists, so that she could bring them a more accurate image of Jamaican arts and culture.

The night that we visited Nanook was a special occasion for the space, a fundraiser and kick off of their United Purpose (UP) Tour, "a curated display of Jamaica's unique and creative cultural arts industries. It is a traveling caravan of eleven artists, all of whom are exceptional in their own fields, venturing into Europe to bring a complete Jamaican experience to the open markets."

And now...a message from our Founder. See you TODAY! @5pm #SupportTheMovement #unitedpurpose #UPTour #LiveArt #CultureExchange

Posted by Nanook on Saturday, June 20, 2015

Some paintings available in the auction at Nanook

Some paintings available in the auction at Nanook

Nanook founder Joan Webley speaking about the Up Tour

That night was filled with incredible performances, art and activities such as live painting and auctions all helping to raise money for the traveling artists that would bring Jamaica out in to the world. There was definitely a more inclusive, and real, sense of community created in this space as we engaged with the art and culture true to the people of Kingston. The Up Tour is a perfect example of a movement that encourages culturally respectful tourism that breaks down the stereotypes of Jamaicans and their arts and culture. Often tourism blurs the lines between invading/exploiting cultures instead of active engagement and discourse, but there are ways that it can be utilized to bring people abroad more authentic images of the island while still bolstering the local economy.

That night was filled with incredible performances, art and activities such as live painting and auctions all helping to raise money for the traveling artists that would bring Jamaica out in to the world. There was definitely a more inclusive, and real, sense of community created in this space as we engaged with the art and culture true to the people of Kingston. The Up Tour is a perfect example of a movement that encourages culturally respectful tourism that breaks down the stereotypes of Jamaicans and their arts and culture. Often tourism blurs the lines between invading/exploiting cultures instead of active engagement and discourse, but there are ways that it can be utilized to bring people abroad more authentic images of the island while still bolstering the local economy.

Many of my initial learning goals or inquiries about Jamaica prior to leaving were met and explored to even higher levels than I had anticipated, giving me even more areas for question, consideration and personal exploration. With what I had learned in Southern Africa last summer, I was very curious to see how the tourism industry affected not only the daily life of the Jamaicans, but also how it shaped their art making and creation of a creative identity post-colonization. Much like what I experienced in Africa, the image of Jamaican art and life has been branded - marketed to travelers through glossy tourism magazines or splashed across television screens in one-dimensional media representations.

I cannot even begin to describe just how much I have learned in the past two weeks. I was exposed to so many new people, places and ideas that have absolutely changed me for the better as a student, an artist, an educator and a person overall. I wish it was possible to summarize in words all of the rich history, art, music and joy I experienced on this journey.

As an art educator, I have grown tremendously through the wisdom and generosity of all the teachers and speakers who were able to share their classrooms and culture with us. Academics aside, there are also countless intangible things I gained from these two weeks that I will take home and carry within me forever. The pure grounding nature and power of such deep, rich and honest art work that we engaged with surely won't leave me any time soon. I am truly so blessed to have had such an amazing opportunity under the guidance of incredible teachers and accompanied by incredible peers.

I cannot even begin to describe just how much I have learned in the past two weeks. I was exposed to so many new people, places and ideas that have absolutely changed me for the better as a student, an artist, an educator and a person overall. I wish it was possible to summarize in words all of the rich history, art, music and joy I experienced on this journey.

As an art educator, I have grown tremendously through the wisdom and generosity of all the teachers and speakers who were able to share their classrooms and culture with us. Academics aside, there are also countless intangible things I gained from these two weeks that I will take home and carry within me forever. The pure grounding nature and power of such deep, rich and honest art work that we engaged with surely won't leave me any time soon. I am truly so blessed to have had such an amazing opportunity under the guidance of incredible teachers and accompanied by incredible peers.

Works Referenced:

Nettleford, Rex M. Mirror, Mirror; Identity, Race, and Protest in Jamaica. Kingston: W. Collins and Sangster (Jamaica), 1970. Print.

Nettleford, Rex M., and Los Angeles California. Caribbean Cultural Identity: The Case of Jamaica : An Essay in Cultural Dynamics. Los Angeles, Calif.: Center for Afro-American Studies :, 1979. Print.

Nettleford, Rex M. Inward Stretch, Outward Reach: A Voice from the Caribbean. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1993. Print.

Nettleford, Rex M. Mirror, Mirror; Identity, Race, and Protest in Jamaica. Kingston: W. Collins and Sangster (Jamaica), 1970. Print.

Nettleford, Rex M., and Los Angeles California. Caribbean Cultural Identity: The Case of Jamaica : An Essay in Cultural Dynamics. Los Angeles, Calif.: Center for Afro-American Studies :, 1979. Print.

Nettleford, Rex M. Inward Stretch, Outward Reach: A Voice from the Caribbean. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1993. Print.